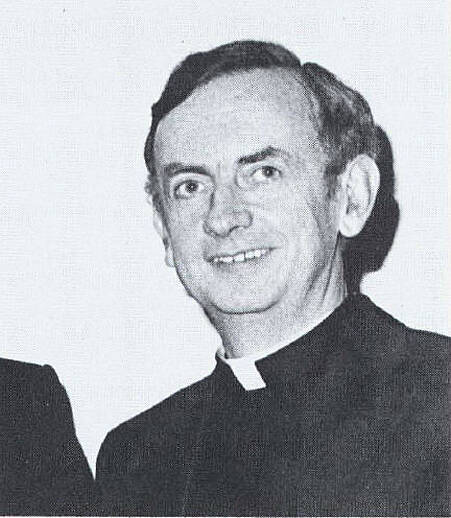

Martin Rafferty, class '55

1936 - 1987

-

Thursday 27 August 1987 was the last day of our golfing holiday. Four of us Vins celebrated mass in the morning. In our reflections after the gospel one of us remarked on a notice in the day’s newspaper. A prominent Irish businessman had died suddenly. He was fifty years old. As is the style, the man’s name and the value of his estate were conjoined in the headline. The words of Psalm 89 came into our reflection: “Make us know the shortness of our life that we may gain wisdom of heart”. On arrival in Dublin that evening the words became piercingly apt when we learned that Martin Rafferty had been found dead in his bedroom in St Pat’s, Drumcondra, in the morning.

Martin was fifty years of age. He was within months of the silver jubilee of his priesthood and within days of the 32nd anniversary of reception into St Vincent’s community. It was a short life. It was also a graciously endowed life. During the requiem mass in St Peter’s, Phibsboro, Martin’s cultural and intellectual qualities were recalled. Our Province is poorer for the passing of one so gifted.

My memories of Martin run on more fraternal lines. Almost my first impression was of his love for music. He was a good pianist, though he preferred to play to an empty hall. He made up for this by being main organist in the Rock chapel. Many of the records in the Students’ hall had his name written on in a schoolboy hand. Halfway through his student years he was touched by the ghost of diminishment. A long illness, which few of us understood, postponed his BA and left him frail and prone to tiredness afterwards. Martin did not enjoy bad health but he did relish this honourable retirement from non-voluntary football. He did, however, participate actively in the life of Glenart. He appeared on stage in the Christmas play each year. After his last performance, in Dial M for Murder, I expressed to him a wicked surprise at his fluency in the part of the slick, cock-tailed, cigarette-holdered Chelsea chap plotting the removal of a surplus wife (me). This, to my mind, contrasted with his earlier, less easy, portrayal of a cranky, skinflint west of Ireland farmer in They got what they wanted. I had imagined, I said, that the latter part would draw on his native Roscommon accents and require less effort. Martin enjoyed the impertinence. He enjoyed laughter and fun.”In laughter we touch an eternal order of Tightness and sanity”.

After two years on the staff in Castleknock Martin was sent abroad to read education in Edinburgh. I was a student in London at the same time. From Scotland he made contact with me, a fellow exile, by letter. Vincent de Paul was a master in the ministry of letter-writing. Martin was Vincentian in this regard, as in much else. A good letter can change the day for someone, it can create a smile and bring joy to the heart. Martin’s regular letters over the years were a mixture of humour, news, wisdom and kindness. In his last letter to me (in March 1987) he chided my silence of one year (Martin expected his correspondents to participate):

And when this creature was thus graciously visited by the uplifting word of his master’s eloquence: in thought most beauteous, most amiable in godly sentiment; (and therein being much comforted), readily and sweetly a warmth in the bowels of compassion did overflow unto streams of thankfulness and divers expostulations of delight such as relieved his spirit mightily and, forsooth, delayed his repair unto the buttery and the modest repast of the mid-day hour! For it seemed that one who had been this twelve month lost (or, perchance, mislaid?) in Afrique lands had been newly discovered alive and he in full possession of his wits! Greater still must be the rejoicing in worthy households of humble clerks and right honest burghers (and some that be less so) when it shall be retailed unto them that he who once did sweetly insinuate sound doctrine, civil probity and elevating speculations (even, ‘tis averred, in the midst of lewd, frivolous and ungodly pomps, shows and cinematographic performances purporting to amuse), this goodly soul should be returned unto them safe and well.

I know no confrère whose letters brought such mirth and enjoyment whether read alone, aloud or circulated among the brethren. His ministry of letter-writing was one of kindness:

Is there anything I can do for you? Are there any tracts, handbills, posters, magazines, comics or digests that would ease Father’s lot and draw his mind to the celestial realms of Tory orthodoxy?

He possessed the hawk-eye of a sub-editor:

Please do something about that hilarious figure at the centre of the community crest at the top of your stationery - it looks like a duck-billed platypus.

For those unversed in primary zoology a platypus is an Australian egg-laying aquatic and burrowing mammal with a ducklike beak and flat tail. Martin would be glad to know that we have indeed done something about our stationery.

While in Scotland Martin used to escape from the chill of John Knox’s Edinburgh to the warm welcome of Dermot Sweeney’s Lanark. There they planned a post-Vatican II parish mission with a four to five man team. It was to last one week. It broke hallowed traditions by siteing itself, apart from Sunday Eucharist to begin and end, outside of the parish church. In the light of years the enterprise was quite inspired: input and discussion groups convened in the hall or in people’s homes, two evenings for street or locality masses in the week, an attempt to involve ministers of other denominations, home visitation of the sick. We invited allsoever to join us in our daily Evening Prayer (this was 1967; we did not yet have the Blue Books).This invitation produced not a solitary response; the four of us were left in this isolation to giggle our way through vespers like seminarists at their first meditatio pomeridiana. The mission was quietly successful and a second one was hosted by Fintan Briscoe eighteen months later.

For this we decided to move our publicity from high to middlebrow. Martin designed a handbill which the Team would distribute after all the Sunday masses. He included a faintly flippant sketch of each of us. There was “our only jailbird – as far as we know” (Frank Mullan); “our Oxford don” (Harry Slowey); “an accomplished musician” (me with guitar, which was both middle-brow and flippant). I cannot recall how Martin styled himself. The distribution went as planned. However, some of those solid Lanark Catholics did not enter into the light-hearted tone of the brochure. A few were puzzled. All the same, our team-spirit maintained its good-humoured zeal. I noticed Martin, by nature shy and a little reserved, flagging towards evening. After the evening mass and distribution he made a declaration of unstinted admiration for our missioners.

There were other experiments at retreats in which he participated in those exciting years, from which the retreat houses and teams evolved. All the same, I am sorry that the inspiration which launched the Lanark enterprise did not continue and evolve.

Martin was not terribly theology-minded. But he was gospel-minded. That wisdom, of heart which we prayed for in the psalm gradually took over his life. This in small ways as well as large. There were his visits with Vincent de Paul groups to the inner city; there was his interest in the seminaire and his weekly session in English (dubbed by himself as “Readin”, writin’ and spellin’”) that was so much appreciated. And on the lighter side there were community outings for meals (and noteworthy here was his Saturday night cook-out at Castleknock), for days out of Dublin or for holidays.

There was the larger wisdom of heart as well. After doing his doctorate in Boston he was appointed as spiritual director in Clonliffe. He found the transition to this work, and to life in a seminary, difficult. It is a necessary task but often it feels aimless and thankless. “My role,” he wrote to me,

seems to be a cross between performing icon and conference- breathing automaton. Everyone thinks you are ‘a good thing’ and (rather like plumbing, running water and sewage) every seminary should have one.

But, significantly, he ended the paragraph on this apparently ill-defined, un-productive and un-rewarding job with this:

Often when I am just about ready to write off what I’m doing the Spirit obtrudes and upsets the even tenor of my cynicism.

Shortness of life and wisdom of heart seem to me the pillars of Martin’s life. In his short life were achievement, kindness and laughter. His life was marked with the cross of Jesus, of which he often spoke; the cross of physical frailty, the cross of restless loneliness, the cross of changes in Church and community and the cross of his “being led where he would rather not go”.

I miss Martin’s cheerful presence among us. I find it difficult, even yet, to absorb that he is not living with us. I know that when I absorb and accept the fact of his death there will remain an absence, a gap in the community that won’t be filled. “Remember, Lord, those who have died…, marked with the sign of faith”.

Padraig Regan CM

MARTIN RAFFERTY CM

Born: Roscommon, 2 December 1936.

Entered CM: 7 September 1955.

Final vows: 8 September 1960.

Ordained a priest in Clonliffe College by Dr McQuaid, archbishop of Dublin, 30 March 1963.

APPOINTMENTS

1963-1982: St Vincent’s, Castleknock.

1982-1985: 4, Cabra Road (studies in Boston).

1985-1987: St Patrick’s, Drumcondra (Clonliffe).

Died 27 August 1987.