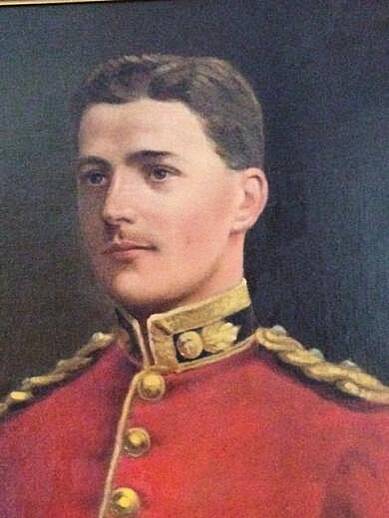

Lt. Joseph Charles Tyndall, Royal Dublin Fusiliers

Centenary Remembrance Tour

Charlie Tyndall was born 18 May 1892 in Dublin, the second of ten children to J.P. Tyndall, a Dublin solicitor and his wife, Ellen, nee Devane.

Of his three younger sisters - the eldest died shortly after birth and the younger two settled after marriage in the UK: Eileen to Dr. Bill McGrath and Florence to Major Dick Murphy, RAMC. His eldest brother was Major General William E. Tyndall, CB, CBE, MC, a surgeon who was awarded the Military Cross in September 1918 - died London 1975.

He had five younger brothers.

Eustace J. Tyndall, who was with the 9th Lancers in France 1916-18, and Captain RASC 1940-45 - died Dublin 1948. Very Rev. Robert J. (Bertie) Tyndall, S.J. - died Dublin 1988. Cecil F. Tyndall, engineer, who married Betty Dowley (whose family sent many sons to Knock), - died Carrick-on-Suir 1977. Donald A. Tyndall, architect who served with the Royal Engineers 1941-45 - died Dublin 1975. Alec D. Tyndall, banker and the youngest in the family - died Dublin 1990.

Charlie's father died 13 February 1916, at the comparatively young age of 57 and Eustace also died young, aged 53, but the rest went on to enjoy good health and long lives. This photograph of the 8 June 1938 wedding of Florence Tyndall to Dick Murphy captures Charlie's eight surviving siblings with their mother.

L-R Back row: Bertie, Eileen, Donald, Mrs Tyndall (nee Devane), Priest, Dick Murphy (groom), Florence (bride), William

L-R Front Row: Eustace, Cecil, Walter (brother of groom), Alec.

For reasons not known now, Eustace was sent to school in England, Ladycross and Beaumont, whereas William, Charlie, Bertie, Cecil and Donald all went to Castleknock College, so 1901 to 1917 saw a continuous flow of Tyndall's at Knock. Alec was next up but by then, his brother Bertie was an established Jesuit, so Alec instead went to Clongowes. It however was only a temporary break, for Alec sent his son David to Knock, class '77.

1902-1927 also saw eight Morrin brothers from Baltinlglass at Knock, who were first cousins of these Tyndall brothers, as their mother Esther was a sister of J.P. Tyndall. Two of these brothers went on to join the Vincentian community, Frederick Vincent, class '16 and Henry, class '27. Another, Joe, class '20, in turn also sent his sons - Peter, class '78 and Michael, class '86. So between the Tyndall's and Morrin's, Charlie had quite the Knock pedigree.

He was with us from 1901 to 1908, when he matriculated as part of the commercial class. Whereas his elder brother William features prominently in academic prize lists in the Chronicles for the period, for Charlie it was athletic prowess that was to the fore. The College didn't play rugby at that time, so Association Football and Cricket were all the rage. Charlie excelled at both, and can be found centre back row in the below photograph.

Junior League Football Champions 1906-07

L-R Back row: N. Lyster, M. Kelly, C. Tyndall, J. Beirne, A. Whitty

L-R Front row: V. Fitzgerald, V. Downes, P. Barry, E. Coffey, C.Daly

Ground: R. Sweeney

Incidentally, the football notes for the 1907 Chronicle, were written by one William J. Morrogh, another famous Knock family from Cork who also had strong connections with the great war. Their father made his fortune with De Beers in South Africa and returned to be MP for Douglas. He sent nine sons to Knock spanning the years 1888 to 1912, six of whom saw active service at the front. The 1915 Chronicle contains a “Letter from the Front” by Lieut. Frank Morrogh, who sadly just a few days later, was killed in action, June 1915, in the Dardanelles. Thankfully the remaining five brothers all returned home safely.

After Knock, in June 1910, Charlie joined the Special Reserve, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, and in 1912 was promoted to Lieutenant.

Standing “inches over six foot and of athletic and muscular build”, he would have cut quite the dashing figure around town, and was frequently mentioned in the society pages, and you get a sense of that from this photo of Charlie alongside his mother attending a Ball in Dublin Castle.

Standing “inches over six foot and of athletic and muscular build”, he would have cut quite the dashing figure around town, and was frequently mentioned in the society pages, and you get a sense of that from this photo of Charlie alongside his mother attending a Ball in Dublin Castle.

Like all young men, Charlie then dreamed of making his fortune, so December 1913, he took one years leave of absence and went down to Australia, initially to his uncle Dean Daniel Devane, and then onwards to a mining concern in Toorak, near Melbourne,

The outbreak of the war put paid to those plans.

"The Australian Table Talk” reported:

A picturesque young soldier is Lieutenant J.C. Tyndall, of the 4th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers, who has lately gone into camp at Broadmeadows as temporary Lieutenant to the Australian Imperial Reserve Force. He came to Melbourne a few months ago on a 12 month leave of absence, intending to remain in Australia for the full period of his furlough, and whilst here became identified with a mining venture which is expected to yield a number of fortunes to the syndicate that holds the patent rights.

But that is another story,

“The best-laid schemes of mice and men gang aft agley”.

Instead of remaining to help the fortune of the fortune-building, Lieutenant Tyndall has answered the War Office call and will soon rejoin his regiment at the front. The Royal Dublin Fusiliers it will be remembered by many, became a bright spot in the public eye at the time of the Boer War, and already it has been heard of in the present campaign, though in sorrowful tones.

The young Lieutenant, who stands well over 6ft, in height and whose youth and pleasing manner and appearance have made him a warm favourite at Toorak, where he has resided, will have charge of the Imperial Reservists at camp and on the voyage to England. Though young in years, he has achieved a good position in the estimation of his superior officers, for not only are his credentials of the highest order, but his tact with his men and his knowledge of the technique of training are such as to make him a man of much promise in the profession he has adopted.

Charlie arrived back in Plymouth on the 18 November 1914 and wrote an article for Irish Life Magazine on his experiences of that voyage from Australia.

On his return, Charlie rejoined his regiment, the 4th Royal Dublin Fusiliers at Sittingbourne, Kent. He crossed the channel on 27 January 1915, and was attached to the 2nd Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles. Within a fortnight of arriving in the trenches, he was killed in action at Kemmel in Belgium on 2 March 1915. He was just 22 years old.

CENTENARY REMEMBRANCE TOUR

His nephews, David Tyndall, class '77 and Richard Murphy organised a family tour to Belgium, around a schedule that would see them arrive at Charlie's grave on the 2 March 2015, 100 years to day after he fell in battle. The Touring Party was made up of David, Richard, their O'Keefe second cousins via the maternal Devane line, and their respective family members as pictured below.

L-R: Mr and Mrs Ted O’Keefe, Lucy Tyndall, John Murphy, Mary Murphy, Katie Tyndall, David Tyndall, Richard Murphy, Jim O’Keefe, Ali Murphy, Charlie Murphy

-

Below are their notes of that two-day trip that focused on eight key locations:

1. TALBOT HOUSE, POPERINGE

“Pop”, as it was commonly known, eight miles to the west of Ypres, was a centre for rest and recuperation being out of range to German artillery. It was filled with shops, cafés, bars, cinemas and places of entertainment. Troops were billeted in the area around. It would have been known to most British soldiers, either on their way to the line or on being relieved.

Talbot House was opened in December 1915 by British army padre, Rev “Tubby” Clayton, as a spiritual retreat. It was known as “Toc H”. The idea was that it should be an oasis of calm, contemplation and respite for exhausted soldiers, away from the base pleasures of the rest of the town. On the top floor there is a chapel, which was known as the “Upper Room”, which is much as it was during the war.

Talbot House was opened in December 1915 by British army padre, Rev “Tubby” Clayton, as a spiritual retreat. It was known as “Toc H”. The idea was that it should be an oasis of calm, contemplation and respite for exhausted soldiers, away from the base pleasures of the rest of the town. On the top floor there is a chapel, which was known as the “Upper Room”, which is much as it was during the war.

Fr. Edward Corbould, of Ampleforth legend, who kindly joined us on the tour, celebrated Mass here on the Sunday morning.

2. LIJSSENTHOEK CWGC CEMETERY

The British and Commonwealth dead were buried near where they died, unlike the French and Belgians who were mostly repatriated. The headstones are uniform in size and inscription. If known, each one displays the rank, name, regimental number and crest, unit, age and date of death. An inscription could be chosen by the family, and the choice of religious emblem. Nearly all the cemeteries have a large Cross of Sacrifice.

Lijssenthoek was the site of several Casualty Clearing Stations during the war. Injured soldiers from the front line would be sent back here to receive medical treatment. The railway line was used for this purpose. Many of the casualties died here, and so this cemetery was here right from 1914.

Lijssenthoek was the site of several Casualty Clearing Stations during the war. Injured soldiers from the front line would be sent back here to receive medical treatment. The railway line was used for this purpose. Many of the casualties died here, and so this cemetery was here right from 1914.

Charlie’s elder brother Willie, also educated at Castleknock, was a doctor in the Royal Army Medical Corps, and worked in CCSs from 1914 onwards, and could well have been at this one.

3. BRANDHOEK NEW MILITARY CWGC CEMETERY

The main reason for this visit was to see the grave of Captain Noel Chevasse, VC and Bar MC, a doctor in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He was an Oxford first class graduate and had run the 400 yards in the 1908 Olympics.

He was one of only three people who have won the Victoria Cross twice. The first was also a doctor in the RAMC, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Martin-Leake, who won the first in the Second Boer War in 1902, and the second in the First Battle of Ypres in 1914. The other one was Charles Upman, and officer in the New Zealand Army, who won both his in the Second World War.

He was one of only three people who have won the Victoria Cross twice. The first was also a doctor in the RAMC, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Martin-Leake, who won the first in the Second Boer War in 1902, and the second in the First Battle of Ypres in 1914. The other one was Charles Upman, and officer in the New Zealand Army, who won both his in the Second World War.

Noel Chevasse’s VCs were awarded in 1916 and 1917, and were both for conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty in action by repeatedly searching for and tending wounded in no-mans land, thus saving many lives. He had previously been awarded the Military Cross for similar conduct in 1915. The 1917 episode was after he had been wounded. He subsequently died of his wounds, and by coincidence, he was treated in the CCS by Captain Martin-Leake.

His headstone is unique in that it displays two Victoria Crosses below his name.

4. SANCTUARY WOOD TRENCH MUSEUM

At the start of the war this was a wooded area well behind the front line, to which fighting units would retire in order to tend the wounded and regroup in relative safety. Hence the name. However as the war progressed the front line got ever closer, and by the 4th Battle of Ypres, the German front line was a mile to the west of here.

There is a CWGC cemetery here which was made after the war. Of the 1,989 servicemen buried there, 1,353 are unidentified. One who is identified is Lieutenant Gilbert Talbot, after whom Talbot House was named. He was killed in July 1915 half a mile from here while serving with the Rifle Brigade, aged 23. His father was the Bishop of Winchester.

The land here has been preserved in the same state as it was at the end of the war, and thus it is the only authentic sector of trenches remaining. It is low lying and drainage is poor. The wet winters during the war meant that the trenches were frequently flooded, and the surrounding area was a sea of mud, made worse by constant shelling. The width of “No Man’s Land” between front lines varied from several hundred to just a few yards.

The land here has been preserved in the same state as it was at the end of the war, and thus it is the only authentic sector of trenches remaining. It is low lying and drainage is poor. The wet winters during the war meant that the trenches were frequently flooded, and the surrounding area was a sea of mud, made worse by constant shelling. The width of “No Man’s Land” between front lines varied from several hundred to just a few yards.

The Ypres area was the busiest during the war, and the trench conditions were the worst, and so it was not a place that soldiers were pleased to be sent to. However they did not spend all their time in the front line, or fighting. Many who survived the war would only have gone “over the top” once or twice. The Army rotated its men constantly, and a soldier would usually spend only ten days a month in a front line position. The rest of the time would be spent behind the lines in reserve, or resting and being resupplied.

5. TYNE COT CWGC CEMETERY

This is the largest British military cemetery in the world. 11,953 are buried here, of whom seventy per cent are unidentified.

The name is said to have come from the Northumberland Fusiliers seeing a resemblance between the German pill boxes which still stand in the cemetery and typical Tyneside workers’ cottages. The Cross of Sacrifice is built on one of these pill boxes.

The cemetery is on slightly raised ground that dominates the land to the west looking towards Ypres, and this line was occupied and fortified by the Germans through much of the war. It was eventually taken in the Third Battle of Ypres in October 1917 by the Australians, after the British and Commonwealth troops had fought for three and a half months. The Canadians went on to take Passchendaele ridge, about a mile from here, in November. There were 285,000 British and Commonwealth casualties over that period.

The cemetery is on slightly raised ground that dominates the land to the west looking towards Ypres, and this line was occupied and fortified by the Germans through much of the war. It was eventually taken in the Third Battle of Ypres in October 1917 by the Australians, after the British and Commonwealth troops had fought for three and a half months. The Canadians went on to take Passchendaele ridge, about a mile from here, in November. There were 285,000 British and Commonwealth casualties over that period.

A few hundred graves were made here soon after it was captured, and after the end of the war it was greatly enlarged when remains were brought in from Passchendaele and from several small burial grounds in the area.

The Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing lists 34,927 names. These are all the British soldiers who fought and died in the Ypres Salient between 17th August 1917 and the end of the war and have no known grave. It was originally intended that all without a known grave would be listed on the Menin Gate in Ypres, but it ran out of space, hence the arbitrary cut off date. Also included are 1,200 officers and men of the New Zealand Forces who died during the same period. All the Canadian missing are named on the Menin Gate. The memorial was completed in 1920.

6. THE MENIN GATE

This was sited here because so many soldiers passed by here on the way to the front. It is one of three memorials to the Missing. The biggest is the Thiepval Memorial which lists over 72,000 names of those who died on the Somme and have no known grave and the third, Tyne Cot, we saw this afternoon.

This was sited here because so many soldiers passed by here on the way to the front. It is one of three memorials to the Missing. The biggest is the Thiepval Memorial which lists over 72,000 names of those who died on the Somme and have no known grave and the third, Tyne Cot, we saw this afternoon.

The Menin Gate Memorial was opened in 1927, and every day since, apart from four years of German occupation in the Second World War, just before eight o’clock in the evening traffic is stopped and the Last Post is played. These days the task is performed by buglers of the local fire brigade, in a moving tribute to those commemorated here.

When he opened the memorial in 1927 Field Marshal Plumer told the relatives:

“He is not missing. He is here”

7. KEMMEL CHATEAU CWGC CEMETERY

2 March 2015. We visited Kemmel on the centenary anniversary of Lieutenant Joseph Charles Tyndall, Royal Dublin Fusiliers being killed in action.

Charlie is buried in Plot 1, Row A, Grave 1. Nobody else in that Row is from the Royal Irish Rifles, nor was anyone here killed at around the same time as him.

Charlie is buried in Plot 1, Row A, Grave 1. Nobody else in that Row is from the Royal Irish Rifles, nor was anyone here killed at around the same time as him.

The cemetery was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens. It dates from the beginning of 1915, but most of the graves were from later in the war when there was heavy fighting around Kemmel in 1918. For a short time the cemetery was in German hands, and it was heavily shelled.

8. ISLAND OF IRELAND PEACE PARK

The tower and surrounding park were built here to commemorate the 16th Irish Division and the 36th Ulster Division fighting here side by side at Wytschaete in June 1917. The memorial honours that unity, and it also honours all Irishmen who were killed or wounded during the war.

It reflects Charlie’s service, because the Royal Irish Rifles, to which he was attached, recruited in the North and became the Royal Ulster Rifles in 1922, while his parent Regiment, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, was from the South.

The tower is of a traditional Irish design, and is made of stone from Tipperary and Mullingar. The park was opened on 11th November 1998, the 80th anniversary of Armistace Day, by Queen Elizabeth II, Irish President, Mary McAleese and King Albert of Belgium.

-