Charlie Tyndall, '08, How the Troops came from Australia

Irish Life Magazine

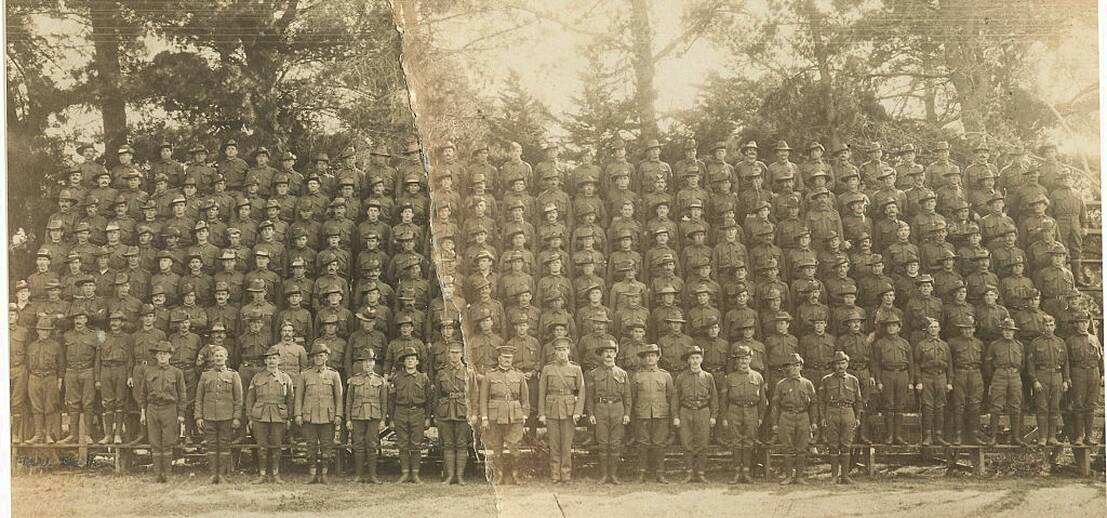

Lt Joseph Charles Tyndall, front centre, in command of the Australian Imperial Reserve Force

Charlie Tyndall, class of 1908, who joined the Royal lrish Dublin Fusiliers after College was in Australia on one years leave of absence when the War Office appointed him to take command of the Australian Imperial Reserve Force as they set sail for Europe. Below is his account of that 1914 trip as was published in Irish Life magazine.

In the beginning of August, I found myself in Melbourne, and on the outbreak of the war was asked by the Defence Department, 3rd Military District, State Military Authority, to accompany the contingent of Imperial Reservists belonging to Victoria and South Australia on their way home. I joined the contingent at the camp at Broadmeadows, about twenty miles from Melbourne. Broadmeadows was chiefly a training camp for recruits, of whom there were about 11,000. The Reservists to whom I was attached were a very fine body of men, many of them cavalry. Both in efficiency, in discipline, and in their exemplary behaviour, they were a useful example to the recruits. These men had nearly all of them given up good positions in Australia to rejoin the colours. Their pay, at least at the beginning, amounted to only 1s. 3d. per day, but this was afterwards made up by the Commonwealth Government to 5s. per day so as to put them on an equality with the ordinary Australian recruit. On the 20th October we entrained for Melbourne and embarked amid a scene of immense enthusiasm. The Australian is certainly not an adept at concealing his feelings, and when he is pleased he lets all the world know it in a most unmistakeable way. Our contingent of Reservists was here broken up; about 700 of the Sydney men went on board the Miltiades, the remainder, including 100 cavalry men, embarked on the Karroo. These men were given the exclusive duty of looking after the horses, of which we had 400 on board; and very well they performed it. It is difficult for anyone who has never seen it tried, to realise what it means to take horses for a long voyage in the tropics and to land 'them alive at their port of destination. Night and day, with the most scrupulous and laborious care, they have to be tended and nursed like babies, but in spite of all care and attention you must reconcile yourself to a percentage of loss. However, whether through good luck or good management our losses were wonderfully small, only 19 out of 400.

At our Australian port of rendezvous we had a rather long wait for the New Zealand squadron, but at last all were complete, and we parted from the Australian continent on the 3rd November - 36 transports and 5 ships of war - and set out on our voyage across the Indian Ocean with all lights darkened. As a rule a voyage across the Indian Ocean in calm weather is a pretty monotonous performance. Day follows day with its regular round of duty and recreation. The men went on with their military training as far as it was possible on board ship: e,g., signalling-, etc. The evenings were given up mostly to boxing and wrestling contests, as we had the fortune to have on board Sapper O'Neill, the well-known army boxer, and Private White the famous wrestler of the Black Watch, who took charge of the proceedings, and the .Australians proceedings some remarkably good talent. Saturday nights were always given up to a concert.

However the monotony of a sea voyage has been alleviated by the genius of Signor Marconi. On the 6th we got a wireless, “North Sea closed to shipping." On the 7th we heard of the unfortunate Valparaiso fight. On the 9th we got a wireless message which produced the most intense excitement,

The Emden was the thought that immediately struck everybody on board. Immediately we saw the Sydney get up full speed and disappear in a cloud of smoke. Another warship belonging to one of our allies also got up full speed and making off in the same direction, but was ordered back and obeyed, apparently with some reluctance. An hour or two later we picked up another wireless message in Low Dutch, “make' for the nearest port". On of our men who was a South African was able to translate the message, and then everybody was really sure that it was really the Emden, and that she was wiring to her collier. We had not long to wait to receive confirmation of our hopes; at 11..30 a.m. we got the message from the Sydney ..

The Emden was the thought that immediately struck everybody on board. Immediately we saw the Sydney get up full speed and disappear in a cloud of smoke. Another warship belonging to one of our allies also got up full speed and making off in the same direction, but was ordered back and obeyed, apparently with some reluctance. An hour or two later we picked up another wireless message in Low Dutch, “make' for the nearest port". On of our men who was a South African was able to translate the message, and then everybody was really sure that it was really the Emden, and that she was wiring to her collier. We had not long to wait to receive confirmation of our hopes; at 11..30 a.m. we got the message from the Sydney ..

We did not see the Sydney again until we anchored in Colombo, when she came in bringing the German wounded and prisoners. We gave her a rousing- cheer; but in doing this we transgressed the wishes of the commodore who had passed the order that, out of regard for the German wounded, there was to be no cheering; but the order, through some mistake, did not reach the Karroo in time.

The remainder of our passage was uneventful. We crossed the line with the usual festivities. We passed through the Red Sea in the usual sweltering heat. We were all inoculated for enteric with the usual unpleasant consequences. At Suez we were delayed for some time through a lack of searchlights. Every ship passing through the canal has to mount a searchlight on her bows, but India had for the time being monopolised the searchlights and Australia had to wait. We had heard many tales of the Invasion of Egypt and had made arrangements for dealing with snipers from the banks of the canal, but when we saw how the banks were held we allowed our arrangements quietly to lapse. At length we anchored off Alexandria and parted with our Australian friends who bade us farewell with the greatest cordiality, not without a touch of envy; but we consoled them with the hope that the Turks would really try to invade Egypt.

From Alexandria home there were no incidents of any importance, a tribute to the thoroughness with which the command of the sea is held by the Allies in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, but in the midst of the present world war, and considering the epoch-making events that are bound to follow from it, he would be indeed an unimaginative individual who could sail the Mediterranean with memories of dead Empires all around, bringing soldiers from the extreme Antipodes to take their place in resisting the latest bid for world power without moralising on the rise and fall of Empires.

One wonders if the men who took part in great events which live in world history were conscious, of the importance of what they did, Did the centurion of Ceasar's 12th Legion realise that his general bore a name that would be spoken of as long as the world endured? Did Scipio Africanus when he subdued and devastated ,the fertile land along whose shores we are sailing realise that he was changing the course of the world's history, and certainly affecting the life and fate of every man in the Northern Hemisphere, who has lived since then?

Such reflections, and many others like them, come naturally to the mind as we pass by the white-walled cities of the land of Hannibal and Jugurtha, looking out from their blaze of sunshine on the blue waters of the Mediterranean as we pass Gibraltar, the great silent sentinel of Empire, as we look up to the hills of Cintra. and think of the great Duke and his "treble rampart lines", as we pass Trafalgar and Finisterre and Corunna, and the many places where one can say:

“Here and here has England helped you,What have you done for England, pray"?

At length we work our way into Plymouth in a gale of wind, and find the Miltiades in before us, which we had last seen in harbour. Our men disembark, and we are sent to our various depots, and I may mention as a rather strange coincidence that this was on the 18th November, the same day at which I had embarked a year ago for Australia.